Mrs Anna Bray: LETTER VII. TO ROBERT SOUTHEY, ESQ.

Crockerntor and the Judge's Chair

Introduction by Prehistoric Dartmoor Walks

We have transcribed this because it is a very early account that is pertinent to a number of things covered on this website. It is from a book published in 1844 but this section, letter (or chapter) 7, is dated 1831 and refers back to journals written in 1802. The main theme is an account of efforts by Mr Bray to find out what happened to the claimed table and chair that was reported to be used by the Stannary parliament on Crockern Tor. In terms of that issue this article includes fascinating accounts from the nearby residents in 1802. The article is couched in the concepts and approaches typical of its day with the usual use and deference to accounts written in Latin by Roman commentators and the description of prehistoric monuments of being "British" (the terminology in usage at the time for the prehistoric) and the erroneous attribution of these sites to druids. However, there is much in this article that is almost modern and of great interest today. The account of prehistoric round houses and pounds could have come from something written in the last few decades. The accounts of Grimspound and the Grey Wethers predate later restoration and are very interesting. The story around the Judge's Chair and the Stannary Parliament involves real detective work and records the knowledge of local people who knew about the events. The description of the tin industry is also of use and the issue of the gathering of lichen to make red dye is something remarked upon by Rev John Swete in his accounts of Spinsters Rock in 1796. Finally a word on spelling and layout. The original spelling is kept here such as "Dennabridge" for Dunnabridge and "Bair-down" for Beardown. For ease of reading some of the longer paragraphs have been broken into shorter paragraphs. The original text has some lengthy footnotes, almost asides, at the bottom of some of the pages, these have been moved to the end.

Bray, Anna Eliza, Letter 7: The Borders of the Tamar and the Tavy, vol.1, (1844)

Bray, Anna Eliza, The Borders of the Tamar and the Tavy, vol.1, (1844)

CONTENTS

- Fabrics of unhewn stone of Eastern origin

- Examples given

- The Gorseddau or Court of Judicature ; its high antiquity

- The solemnity of trial

- Druid judges in civil and religious causes

- Courts of Judicature held in the open air with the nations of antiquity

- Crockerntor or Dartmoor

- Such a Court in the Cantred of Tamare

- Since chosen for the Court of the Stannaries

- Account of Crockerntor in ancient and modern times

- Tin traffic

- Stannaries, etc.

- The Judge's chair

- Parliament-rock, etc, described

- Longa-ford Tor

- Rock basin

- Many barrows on Stennen Hill

- A pot of money, according to tradition, found in one of them

- Bair-down Man, or British obelisk

- The Grey Wethers ; stones so called

- Causes for Crockerntor being chosen by the Stannaries for their Parliament

- Probably the Wittenagemot of this district succeeded on the very spot where the Gorseddan was held in British times

- Grimspound a vast circular wall; its antiquity

- Account of similar structures by Strabo and Caesar

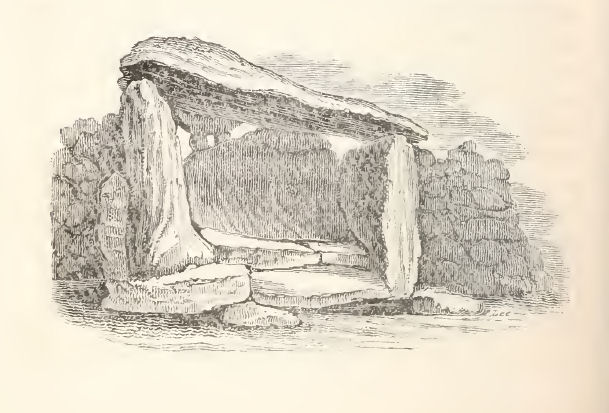

- Arthur's Stone, a British structure of great interest

- Flocks and herds of the Britons

- Tin traffic

- The scarlet dye mentioned by Pliny, probably alluding to the scarlet moss, from which dyes are formed, on the Moor

- Excursion in search of Dennabridge pound

- Horses in their free state

- The river at Dennabridge

- Judge Buller exonerated from having re-moved the great stone, used as a table by the old Stannators at Parliament-rock

- The stone found at last far from its original station

- Dennabridge pound, its extent, etc, described

- Trunk of an oak tree, found by Hannaford, in a bog

- Oak bowls found in a bog on the Moor; their great antiquity

- River Cowsick

- Inscription to Shakspeare on the rock below the bridge.

Vicarage, Tavistock, March 9th, 1832.

MY DEAR SIR, I PURPOSE in this letter giving you some account of a place on Dartmoor which, it is most probable, was used in the days of the Britons as a tribunal of justice. Unhewn stones and circles of the same, it is generally admitted, were raised for courts of this description; and we have the most ancient and undoubted authority - the Bible, for considering that fabrics of unhewn stone derive their origin (like the more rational parts of the religion of the Druids) from those eastern nations of which the Celtae were a branch.

We find that the custom of erecting, or of consecrating monuments of this nature as memorials of a covenant, in honour of the dead, as places of worship, etc, prevailed even from the earliest times. Jacob and Laban made a covenant in Gilead; and no sooner was this done, than "Jacob took a stone and set it up for a pillar."Joshua in passing over Jordan with the ark caused a heap of stones to be raised, that they "should be for a memorial unto the children of Israel for ever."And certain tribes also "built there an altar by Jordan, a great altar to see."And after Joshua had destroyed Achan, "they raised over him a great heap of stones unto this day."The Jewish conquerors did the same by the King of Ai; and on Absalom "did they heap stones:"and Rachel's monument, the first we read of in the Bible, was of stone, for Jacob "set up a pillar upon her grave." 1

There cannot, I think, be a doubt that the courts, as well as the temples of unhewn stone, had their origin in the East. And as the laws of the British people were delivered to them by the Druids, not as secular ordinances, but as the commands of the gods whom they adored, this circumstance no doubt added to the solemnity of their administration : so that it is not improbable the spot appointed for the Gorseddau or Court of Judicature was chosen with a view to the most advantageous display of its august rites. Hence an elevated station, like the temples of their worship, became desirable; and there must have been a more than ordinary feeling of awe inspired in the mind of the criminal, by ascending heights covered, perhaps, with a multitude, to whose gaze he was exposed, as he drew nigh and looked upon those massive rocks, the seat of divine authority and judgment.

How imposing must have been the sight of the priesthood and their numerous train, surrounded by all the outward pomps and insignia of their office; as he listened, may be, to the solemn hymns of the Vates, preparatory to the ceremonial of justice, or as he stept within the sacred enclosure, there to receive condemnation or acquittal, to be referred to the ordeal of the logan, or the tolmen, according to the will of the presiding priest! - As he slowly advanced and thought upon these things, often must he have shuddered and trembled to meet the Druid's eye, when, to use the words of Ossian, he stood by "the stone of his power."

The Druids not only adjudged, but with their own hands executed the terrific sentence they had decreed. The human victims which they immolated to appease, or to render propitious their deities, (particularly those offered to Hesus the God of Battles, and to Bel, or the Sun,) were generally chosen from criminals; unless when the numbers demanded by the sacrifice induced them to mingle the blood of the innocent with that of the guilty, to supply their cruel rites. And as these sacrifices were not merely confined to the eve of a battle, or to make intercession for the calamities of a kingdom, but were frequently offered up at the prayer of any chief or noble afflicted by disease, it is not unlikely that the condemned criminal was hurried from the Gorseddau to suffer as a victim to the gods, against whose supreme will all crimes were held to be committed that were done upon the earth.

That these ancient courts of justice were kept in the open air seems to be the most probable opinion, since such was the custom with many of the nations of antiquity; the Areopagus of the Greeks is an instance. And in earlier ages we find it to have been much the same; as we read in the Bible of the elders pronouncing judgment "sitting in the gates."These gates were at the entrance of a town or city; a court that must have been in some measure held in the open air. With the Celtic nations it was unquestionably a practice that long prevailed amongst their posterity; since, in the ancient laws of Wales, the Judge was directed "to sit with his back to the sun or storm, that he might not be incommoded by either."2

One of these primitive courts, handed down as such by successive ages from the earliest times, through the various changes of government and religion, is to this day found on Dartmoor: it is known by the name of Crockerntor,3 the most curious and remarkable seat, perhaps, of Druidical judicature throughout the whole kingdom. It remained as the Court of the Stannaries till within the last century, and hence was it commonly called Parliament-rock. On this spot the chief miners of Devon were, by their charters, obliged to assemble. Sometimes a company of two or three hundred persons would there meet, but on account of the situation, after the necessary and preliminary forms had been gone through, they usually adjourned to Tavistock, or some other Stannary town, to settle their affairs. The Lord Warden, who was the Supreme Judge of the Stannary Courts, invariably issued his summons that the jurors should meet at Crockerntor on such a day; and by an accidental reference to an old magazine, I find a record of a meeting of this nature having been there held so late as the year 1749. If this was the last meeting or not, I cannot say, but I should think not, and that the custom died gradually away, till it was altogether abolished.

Some powerful motive, some deep veneration for ancient usages, or some old custom too well established to be easily set aside, must have operated to have caused these Stannary Courts, in comparatively modern times, to be held on such a spot as Crockerntor; whose rocks stand on the summit of a lofty height open on all sides to the bleak winds and to the weather, affording no shelter from a storm, remote from the habitations of men, and, in short, presenting such a combination of difficulties, and so many discomforts to any persons assembling on matters of business, that nothing can be more improbable, I had almost said impossible, that such a place should have been chosen for the Stannary Courts, had it not been handed down as a spot consecrated to justice from the earliest ages.

Having offered these few introductory remarks on the subject of Crockerntor, I now give you the following extracts from Mr. Bray's journal of his survey of the western limits of Dartmoor, so long ago as the year 1802; when, though a very young man, he was the first person who really examined and brought into notice many of those curious Druidical antiquities in which it abounds. He spoke of them in various quarters; and some persons were induced, by what he said, cursorily to explore them. Of these a few, now and then, published some account, and though not unfrequently availing themselves of Mr. Bray's information, I do not know, excepting in one instance, that any person ever did him the justice to acknowledge the obligation, or even to mention his name as having been the first to lead the way to an investigation of what was still to be found on the moor : -

EXTRACT FROM THE JOURNAL.

"September 20th, 1802. Crockerntor, or Parliament-rock, is situated on Dartmoor, near the turnpike-road leading from Moreton to Tavistock, at the distance of about eleven miles from the former, and nine from the latter. Prince, in his 'Worthies of Devon,' p. 168, in his account of the family of Crocker, after informing us that Crockernwell received its name from them, says - 'There is another famous place in this province, which seems to derive its name also from this family, and that is Crockerntor, standing in the forest of Dartmoor, where the parliament is wont to be held for Stannary causes; unto which the four principal stannary towns, Tavistock, Plimton, Ashburton, and Chagford, send each twenty-four burgesses, who are summoned thither when the lord warden of the Stannaries sees occasion: where they enact statutes, laws, and ordinances, which, ratified by the lord warden aforesaid, are in full force in all matters between tinner and tinner, life and limb excepted. This memorable place is only a great rock of moorstone, out of which a table and seats are hewn, open to all the weather, storms and tempests, having neither house nor refuge near it, by divers miles. The borough of Tavestock is said to be the nearest, and yet that is distant ten miles off.'

"I am not inclined to agree with Prince about the origin of the name of this rock, nor, from the present appearance of it, do I think his a correct description. The first thing that struck me was a rock, with a fissure in the middle, with one half of it split, either by art or nature, into four pretty regular steps, each about a foot and a half high and two feet broad.4 Whether these were used as seats of eminence at the assembly of the tinners, I cannot pretend to say.

"Before this mass, towards the north, is a short ledge of stones evidently piled up by art, which might have been a continued bench. On ascending higher, I arrived at a flat area, in which, though almost covered with rushes, I could plainly trace out four lines of stones forming an oblong square, twenty feet in length and six in breadth, pointing nearly east and west. The entrance seems to have been at the north-west corner. At the north side, four feet distant, is another imperfect line, and ten feet on either side is a straight natural buttress of rock. Possibly the table might have stood in the centre of this area, and these lines may be vestiges of the seats around it. I can hardly suppose the stone was so large as to rest on these as its foundation, though there are no stones in the middle that might have answered that purpose. Whilst the Lord Warden and Stannators presided at this table, probably the rest of the assembly filled up the remainder of the area, or climbed the rocks on each side.

"As an instance of the powers of the Stannary Court, I have been informed that a member of the House of Commons having spoken in it of the Stannaries in a manner that displeased the Lord Warden, as soon as the offending member came within the jurisdiction of his court, he immediately issued his precept, arrested him, and kept him in prison on bread and water till he had acknowledged his error and begged pardon for his transgression.

"Tin, on being melted, is put into moulds, holding generally somewhat above three hundred weight (then denominated block-tin), where it is marked, as the smelters choose, with their house-mark [that brought to Tavistock bears, I have generally observed, an Agnus Dei, or lamb holding a pennon] by laying brass or iron stamps in the face of the blocks while the tin is in a fluid state, and cool enough to sustain the stamping iron. When the tin is brought to be coined, the assay-master's deputy assays it by cutting off with a chisel and hammer a piece of one of the lower corners of the block, about a pound weight, partly by cutting and partly by breaking, in order to prove the roughness [query toughness?] and firmness of the metal. If it is a pure good tin, the face of the block is stamped with the duchy seal, which stamp is a permit for the owner to sell, and, at the same time, an assurance that the tin so marked has been examined and found merchantable. The stamping of this impression by a hammer is coining the tin, and the man who does it is called the hammer-man. The duchy seal is argent, a lion rampant, gules, crowned, or with a border garnished with bezants."See Rees’ Ency.

The punishment for him who, in the days of old, brought bad tin to the market, was to have a certain quantity of it poured down his throat in a melted state.

Tin was the staple article of commerce with the Phoenicians, who used it in their celebrated dye of Tyrian purple, it being the only absorbent then known. This they procured from the Island of Britain. Its high value made the preservation of its purity a thing of the utmost consequence; any adulteration of the metal, therefore, was punished with barbarous severity. The Greeks were desirous of discovering the secret whence the Phoenicians derived their tin, and tracked one of their vessels accordingly. But the master of her steered his galley on shore, in the utmost peril of shipwreck, to avoid detection; and he was rewarded, it is said, by the State for having preserved the secret of so valued an article of national commerce.

The next extract I here send you is from Mr. Bray's Journal of June 7th, 1831.

"My wife, her nephew, and myself, set out from Bairdown, between twelve and one o'clock, for Crockerntor. In addition to the wish she had long felt of seeing it, her curiosity was not a little raised by my tenant's telling her that he could show her the Judges Chair. And I confess that my own was somewhat excited to find out whether his traditionary information corresponded with my own conjectures, made many years ago, as to this seat of the president of the Stannators. He took us to the rock (situated somewhat below the summit on the south side of the Tor) which bears the appearance of rude steps, the highest of which he supposed to be the seat. It seems to be but little, if at all, assisted by art, unless it were by clearing away a few rocks or stones. Below it is an oblong area, in which was the table, whilst around it (so says tradition) sat the court of Stannators: whence it is also known by the name of Parliament-rock. This stone, I had been informed, was removed by the late Judge Buller to Prince Hall; but my tenant told me that it was drawn by twelve yoke of oxen to Dennabridge, now occupied by farmer Tucket, on the Ashburton road, about ten miles from Tavistock. It is now used, he said, as a shoot-trough, in which they wash potatoes, etc.

"From this, as far as I can comprehend his meaning, I should conceive that it serves the purpose of a lip, or embouchure, to some little aqueduct that conveys the water into the farmer's yard. The Tor itself is of no great height, and is now much lower than it was, by large quantities of stone having been removed from its summit for erecting enclosures and other purposes. It could not be chosen, therefore, for its supereminent or imposing altitude; though possibly it might be so for its centrical situation; but I am disposed to think that it was thus honoured from being used as a judicial court from time immemorial. My reasons I shall mention hereafter. I shall remark here, however, that it is the first tor of any consequence that presents itself on the east side of the Dart, upon the ridge that immediately overhangs its source.

"We then proceeded along this ridge to Little Longaford, or Longford Tor. This, in Greenwood's map, which is defective enough in regard to names, is thus distinguished from a larger one; whilst the tors that follow Crockerntor in succession are there called Littlebee tor, Long tor, Higher-white tor, and Lower-white tor. White tor, or Whitentor, as my tenant pronounced it, we did not visit; and as I have some doubts about the real names of the tors, I shall only say that the first (a small one) that we approached had something in its appearance which so much reminded me of Pewtor, that I asked the guide if there were any basins in it: at first he replied in the negative, but afterwards said he thought he had once observed a basin on one of these tors.

“This was enough to ensure a search, and we were not long in finding one. It was in the shape of a rude oval, terminating in a point or lip, about twenty inches long, eighteen wide, and six deep. A square aperture among the rocks here, somewhat like a window, suggested the idea of its possibly having been used as a tolmen, through which children, and sometimes, I believe, grown people, were drawn to cure them of certain diseases. The second tor was much less, but large enough to afford Mrs. Bray, who felt fatigued, sufficient shelter from the sun and wind whilst we proceeded; and there we left her busied with her sketch-book.

"Between this and the great tor we found several pools of water, though it was the highest part of the ridge, and though the season had been so free from rain (a circumstance not very common in Devonshire) as not only to render the swamps of Dartmoor passable, but almost to dry up the rivers. Longford Tor is more conical than most of the eminences of the forest, having very much the appearance of the keep of a castle. Unlike also the generality of tors, which mostly consist of bare blocks of granite, it has a great deal of soil covered with turf, and only interspersed with masses of rock, whilst the summit itself is crowned with verdure. Towards the north is White or Whiten Tor: for the Devonians soften, or, as some may think, harden, words by the introduction of a consonant, but more frequently of a vowel; and they arc laughed at for saying Black-a-brook instead of Blackbrook, though we perceive nothing objectionable in Black-a-moor, which is precisely upon the same principle of euphony. On this tor, some years ago, were found some silver coins, and, I believe, human hair. And on Stennen hill, which lies below it, if I may trust my informant, are many barrows, in one of which was supposed to have been found 'a pot of money,' whilst two men of the name of Norrich and Clay were employed in taking stones from it. The former, it is said, discovered it without communicating it to his companion, but sent him to fetch a 'bar-ire,' or crow-bar, whilst he availed himself of the opportunity to appropriate the contents to himself. The inference seems principally to be drawn from the circumstance that he afterwards was known to lend considerable sums of money at interest.

"The greatest extent of view from Longford Tor is towards the east and south-east. In that direction, as far as I could collect, you see Staple Tor (so that there seems to be two of this name on the moor), High, or Haytor, Bagtor, Hazeltor, etc. On Haytor (which is commonly called Haytor rocks), though at so great a distance, is visible a kind of white land or belt about its base, made by the removal of granite: so that we can more easily account for it than those of Jupiter. Of the tors that lie towards the south and south-west, Hessory is certainly higher than Longford (which my guide at first doubted), as also Mistor. Nearer are Bair-down and Sidford tors.

“Bair-down-man (which, however, we could not see) is a single stone erect, about ten feet high. To these succeeded, towards the north, Crow, or Croughtor, and Little Crowtor. I learnt from my guide that at a place called Gidley there are circles much larger and far more numerous than near Merrivale. There are also two parallel lines about three feet apart, which stretch to a considerable distance. In order to see them, you must go to Newhouse, about twelve or thirteen miles on the Moreton road from Tavistock, and there turn off into the moor for about four or five miles. I also learnt that near the rabbit warren there is something that goes by the name of the King's Oven.

"We again on this day visited Wissman, Wistman, or Welshman's Wood (concerning the etymology of which I have some remarks in my former papers): it is about half a mile in extent, and consists principally of oaks, but is here and there interspersed with what is called in Devonshire the quick-beam or mountain-ash. I conceive it to have been the wood of the Wise-men, and Bair-down, on the opposite side, the Hill of Bards. On the latter were formerly many circles, which, I am sorry to say, were destroyed by the persons employed by my father in making his enclosures. Would they have given themselves but a little more trouble they might have found a sufficient supply among those stones or rocks which are thickly scattered on a spot opposite the wood, and to which they give the name of the Grey Wethers. I think that the same name has been given to some stones at Abury, with which is supposed to be erected Stonehenge. If so, the coincidence is not a little remarkable. They possibly may be so called from resembling at a distance a flock of sheep. The resemblance indeed had struck me before I heard the name.

"I shall now state the reasons why I think Crockern Tor was chosen by the miners as the chief station for holding their Stannary Courts. It is but little more than a mile from what I venture to consider as the Hill of Bards and the Wood of Wisemen, or Druids. On, or near each of these are numerous circles, which, whether they were appropriated to domestic or religious purposes (most probably to both), clearly indicate that it must have been a considerable station. This was not only supplied with water from the river, but two or three springs arise from the rocks at the bottom of the wood itself.

“Well sheltered and well watered (for not only had they trees to screen them from the storm, but they had also a comparatively snug valley, open only to the south), it is no wonder that the aborigines here fixed their habitation. The circles, the wood, the existing names, all seem to lead to the supposition that some of the high places in their immediate, neighbourhood were originally those of superstition and judicature, where priest, judge, and governor were generally combined. The tor that we may thus imagine was appropriated by the ancient Britons, might afterwards (from traditionary veneration for the spot) be used by the Saxons for assembling together their Wittenagemot, or meeting of Wisemen, and lastly, for a similar reason, by the miners for their Stannary Courts.''

Before I give you Mr Bray's account of Dennabridge Pound, which will be the next extract from his Journal, it may not be amiss to observe that there is on Dartmoor another remarkable vestige, and one better known, of like antiquity, called Grimspound. Like that of Dennabridge, this truly cyclopean work is an enclosure, consisting of moor stone blocks, piled into a vast circular wall, extending round an area of nearly four acres of ground. Grimspound has two entrances, and a spring of water is found within, where the ruins of the stone-ring huts are so numerous as to suggest the idea of its having been a British town. It is well known that the foundations of all these primitive dwellings were of stone, though their superstructure, according to Diodorus and Strabo, was of wood. For they "live,"says the former, "in miserable habitations, which are constructed of wood and covered with straw."And, when speaking of the Gauls, the latter says, "they make their dwellings of wood in the form of a circle, with lofty tapering roofs."

In some instances it is not improbable that the larger stone circles are vestiges of enclosures made for the protection of cattle. The Damnonii were celebrated for their flocks and herds; and the wolves, the wild cats, and the foxes, with which this country once abounded, must have rendered such protection highly necessary for their preservation. I have often remarked on Dartmoor two or three small hut-rings, and near them a larger circle of stones; the latter I have always fancied to have been the shelter of the flocks, and the former the dwellings of their owners. There is nothing perhaps very improbable in this conjecture: since many tribes of the ancient Britons were, like the Arabs, a wandering and a pastoral people ; and it is also worthy observation, that to this day the Devonians never fold their sheep; but, on Dartmoor in particular, still keep them within an enclosure of stone walls set up rudely together without cement. Where extensive stone circles are found near what may be called a cursus, or via sacra (of which I shall have much to say hereafter), or near cromlechs and decaying altars, we may fairly conclude such to have been erected not as the habitations of individuals, but as temples sacred to those Gods whose worship would have been considered as profaned within any covered place, and whose only appropriate canopy was held to be the Heavens in which they made their dwelling.

The circles within Grimspound are different from these; and that this vast enclosure (as well as Dennabridge Pound) was really a British town, seems to be supported by the accounts given of such structures by Strabo and Caesar. The latter describes them as being surrounded by a mound or ditch for the security of the inhabitants and their cattle. And Strabo says, "When they have enclosed a very large circuit with felled trees, they build within it houses for themselves and hovels for their cattle." 5

That the people of Dartmoor should prefer granite to felled trees for such an enclosure is nothing: wonderful, inasmuch as the moor abounds with it: in fact it must have been then, the same as in the present day, a much easier task to have piled together the blocks and pieces of stone, strewed all around them, than to have felled trees for the purpose of forming their walls; and how much greater was the security afforded by a granite fence, to one of mere timber! In other parts of Britain, such as Caesar saw and described, rock or stone was not so easily or so plentifully to be found. The Britons, therefore, very naturally availed themselves of what the country would most readily afford; and the wild and vast forests supplied materials for their public walls as well as their private dwellings.

Stones, however, it is probable, were in all places considered as indispensable in the erection of those structures sacred to the rites of religion; and hence is it that we often see such enormous masses piled on places where it seems little less than miraculous to find them : for no stones of a similar nature being seen in their immediate neighbourhood, gives rise to the belief that they must have found their present stations by being moved from a distance, and not unfrequently to the summits of the loftiest hills and mountains: such, for instance, is that most extraordinary cromlech called Arthur's Stone on the eminence of Cevyn Bryn in South Wales. 6 That most of these structures were of a sacred nature cannot well be doubted. No impulse either on the public or the private mind is so strong as that dictated by a feeling of religion, even when it is misdirected: no labours, therefore, have ever equalled those of man when he toils, in peace or in war, for the honour or the preservation of his altars.

That Grimspound and Dennabridge sheltered both the Britons and their cattle seems the more probable when we recollect the general customs of that people, and of the Damnonii in particular; since, in every way, their flocks must have been to them of the highest value. They were allowed to be the most excellent in Britain; the constant verdure of this county no doubt rendered them such. They were not merely useful at home, but an article of commerce abroad; and Caesar says, that "the Britons in the interior parts of the country were clothed in skins."It is not improbable, therefore, that the Damnonii found their account in the wool and skins of those flocks for which they were so famed, as a convenient clothing for their neighbours.

Their tin traffic with the Phoenicians had early initiated them into a knowledge of the advantages and benefits of commerce. And as I have long taken a pleasure in busying myself to trace out, in connexion with ancient times, whatever may be found in nature or in art on Dartmoor, I amuse myself with fancying that I have discovered an allusion in Pliny to the beautiful and scarlet moss still found on the moor, which, not many years ago, was used as a dye for cloth. Indeed, it is not improbable that, as such, it became an article of commerce even in the days of the ancient Britons; for Pliny says, when speaking of British dyes, that they were enriched by "wonderful discoveries, and that their purples and scarlets were produced only by certain wild herbs."

How sadly have I rambled in these pages! It is a good thing that in letters there is no sin in being desultory, or how often should I have offended! But letters are something like the variations of an air of music; you may run from major to minor, and through a thousand changes, so long as you fall into the subject at last, and bring back the ear to the right key at the close. Once more, therefore, I fall back on Dennabridge Pound, and here follows the extract from Mr. Bray's journal: -

"On the 25th of July, 1831, I set out in search of two objects on the moor; namely, the table, said to have been removed from Crockern Tor, and Dennabridge Pound, which (like all, or most others on the moor) I had understood was on the site of a Celtic circle. On going up the hill beyond Merrivale bridge, some horses and colts, almost wild, that were in an inclosure near the road, came galloping towards us, and, either from curiosity or the instinctive feeling of sociability, kept, parallel with the carriage as far as their limits would allow. One of them was of a light sorrel colour; whilst its mane, which was almost white, not only formed a fine contrast, but added considerably to the picturesque effect of the whole by its natural clusters waving and floating, now in the air, now adown its neck, and now over its forehead, between its eyes and ears. My attention, perhaps, was the more directed to it, from having previously asked my servant who drove us, why the manes of my ponies were turned in opposite directions, as I thought (though I possibly may be mistaken) that it was one, among many other cavalry regulations, that the mane of a horse should turn differently from that of a mare. He seemed to recognise the rule by his reply, which was, that he could not get the mane of one of them to lie on the proper side. I could not help thinking that we deformed our horses by cropping their manes and tails, besides cruelly depriving them of their natural defence against flies. And enthusiastically as I admire the taste of the Greeks, particularly in sculpture, I cannot but confess that, if I may be allowed to consult my own eyes for a standard, they seem to have violated true taste and rejected a rich embellishment, in representing, as on the Elgin marbles in the British Museum, all their horses with hogged manes. Having thus run from painting to sculpture, and from England to Greece, though it may still, perhaps, be traced to association of ideas, I must be allowed to return to those connected with our native soil, and somewhat, perhaps, with the objects of our present pursuit (which may account also, accumulatively, if more apologies be wanting, for these digressions), by stating that I had but a little before remarked, en badinant, to my wife, that she might fancy herself Boadicea hastening in her war-chariot to meet the Druids in their enchanted circles.

"Near a bridge, over which we had passed, I observed, on the right of the road, a circle, seven paces in diameter, with a raised bank around, and hollow in the centre. Having come about ten miles from Tavistock, which I had understood was the distance of Dennabridge Pound, I entered a cottage near, to make inquiries for the object of our pursuit, but could gain little or no information, finding only a girl at home who had not long resided there. I had observed on the map that there was not only Dennabridge Pound, but also a place called Dennabridge. which I learnt from this girl was about a quarter of a mile distant. Seeing nothing at the former place that at all corresponded with the object of mv search, I resolved on proceeding to the latter; not without hopes that I should meet with some kind of primitive bridge, consisting perhaps of immense flat stones, supported on rough piers, which was the ordinary construction of our ancient British bridges.

"Seeing a person whom I considered one of the natives near a cottage, I pointed to a lane that seemed to lead towards the river, and asked if it was the way to Dennabridge. The answer I received was, 'This, Sir, is Dennabridge.' My informant seemed as much surprised at my question, as I was at his reply, and we both smiled, though probably for different reasons. No signs of one being visible, I inquired (and I think naturally so) where was the bridge that gave name to the place? He said that he knew not why it was so called, but that there was no bridge near it. Observing, however, at some distance down the river, what seemed not unlike the piers of one, of which the incumbent stones or arches might have fallen, I asked if a bridge had ever stood there. He believed not, but said that they were rocks; situated, however, so near each other, that it was the way by which persons usually crossed the river. Understanding that the spot was difficult of access, particularly for a lady, we did not go to it; but I am rather disposed to think that the place is not so called, as was lucus a non lucendo, but that these rocks were considered as a bridge, or at least quasi a bridge. And perhaps it deserved this name as much as that which is thus mentioned by Milton in his description of Satan's journey to the earth.

‘Sin and Death amain,

Following his track, such was the will of Heaven,

Paved after him a broad and beaten way

Over the dark abyss, whose boiling gulf

Tamely endured a bridge of wond'rous length,

From Hell continued, reaching the utmost orb

Of this frail world.’

"On further conversation with this man, I learnt that he lived at Dennabridge Pound, where there was no stone of the kind I inquired for, but that at Dennabridge itself, hard by, was a large stone that possibly might be the one in question. I asked if he had ever heard that it had been brought thither by the late Judge Buller. He said that it must have been placed there long before the judge’s time; that he knew the judge well, and had lived in that neighbourhood forty years or more. Perhaps I might have obtained the information I wanted long before, had I asked for what I was told to ask; namely, for a stone that was placed over a shoot. But, absurdly, I confess, I have always had an objection to the word; because, in one sense at least, it must be admitted to be a vulgarism even by provincialists themselves. The lower classes in Devonshire, almost invariably, say shoot the door, instead of shut the door. And when it is used by them to express a water-pipe, or the mouth of any channel from which is precipitated a stream of water, I have hitherto connected it with that vulgarity which arises from the above abuse of the word. But if we write it, as perhaps we ought, shute, from the French chute, which signifies fall, we have an origin for it that may by some, perhaps, be considered the very reverse of vulgar, and have, at the same time, a definite and appropriate expression for what, otherwise, without a periphrasis, could hardly be made intelligible.

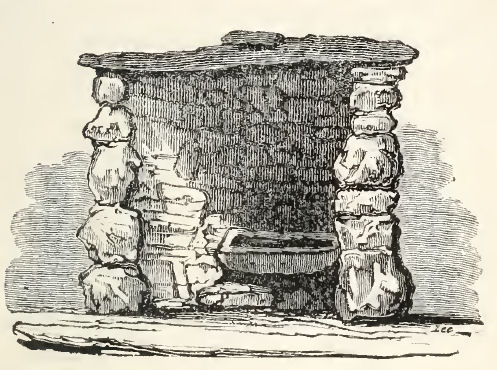

“At the entrance of the farm-yard adjoining, is, I doubt not, the stone I had gone so far in search of, though I could not gain such satisfactory information as I anticipated. The farmer who lives on the spot exonerates the Judge, as did my first informant, from having committed the spoliation with which he has been charged. He says that it has been there, to his own knowledge, for fifty years; and that he has heard it was brought from Crockern Tor about eighty years ago. He further says that it was removed by the reeve of the manor. His wife, who is the daughter of this reeve (or his successor, I do not remember which), says that she, also, always heard that it had been brought from Crockern Tor, but she does not think that it could have been the table, as she remembers that her father used to take persons to the spot as a guide, and show them the table, chair, and other objects of curiosity on the tor. I thought I could perceive that the reeve of the manor was at any rate considered a great personage, and not the less so, perhaps, by being the Cicerone, or guide to the curiosities of the forest ; for this is the word by which the inhabitants are fond of designating the treeless moor. I do not know whether the reeve, with the spirit of an antiquary, had any veneration for a cromlech, and therefore wished to imitate one ; but, if such were his intention, he succeeded not badly: for the stone (which is eight feet long by nearly six wide, and from four to six inches thick) is placed, as was the quoit in such British structures, as a cover, raised upon three rude walls, about six feet high, over a trough, into which, by a shute, runs a stream of water.

And probably the idea that the removal of this stone was by someone in authority, may have given rise to the report, that such person could be no less than Judge Buller, who possibly might be supposed to give sentence for such transportation (far enough certainly, but not beyond sea), in his judicial capacity: to which, perhaps, some happy confusion between him and the judge or president who sat in the Stannary Court may have contributed. Nay, possibly the reeve or steward may have considered himself to be the legal representative of the latter, and to have removed it to his own residence. We thence returned to Dennabridge Pound. On clambering over the gate, I was surprised to find close to it a rude stone seat. Had I any doubt before that the pound was erected on the base of an ancient British, or rather Celtic circle, I could not entertain it now: for I have not the slightest doubt of the high, antiquity of this massy chair. It is not improbable that it suggested the idea of the structure over the trough. And it is fortunate that the reeve had not recourse to this chair, instead of the stannary table, for the stone he wanted. It certainly was handier; but possibly it would have deprived him of showing his authority and station by occasionally sitting there himself. But I am fully convinced that it was originally designed for a much greater personage; no less perhaps than an Arch-Druid, or the President of some court of judicature.

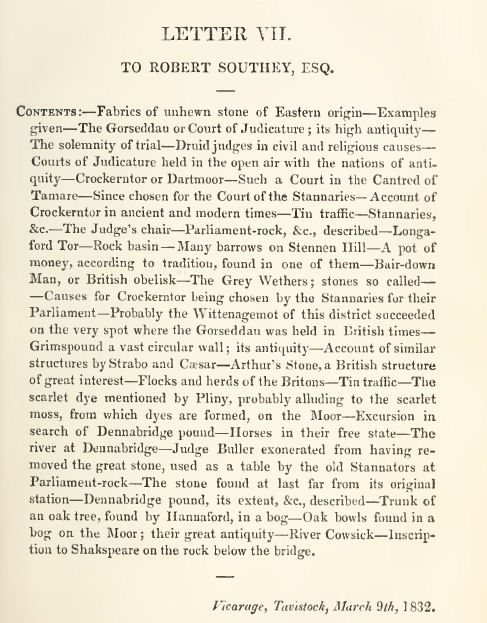

Two upright stones, about six feet high, serve as sides or elbows. These support another, eight feet long, that forms the covering overhead. The latter, being in a sloping direction, to give greater shelter both from wind and rain, extends to the back, which consists also of a single stone. In front of it are two others, that supply the immediate seat, whilst a kind of step may be considered as the foot-stool.

"The enclosure, pound, or circle, is about 460 paces in circumference on the inside. The wall of it has a double facing, the external part being a little higher than the inner. Though far beyond the memory of man, this superstructure is unquestionably modern, when compared with the base or foundation, which is ruder, and of larger stones. There are a few rocks scattered about in the area. I thought, however, that I could distinguish the vestige of a small circle near the centre, through which passed a diametrical line to the circumference, but somewhat bent in its southern direction towards the chair.

"On reaching Bair-down, I was told by my tenant Hannaford, that there could be no doubt but I had seen the right stone, and that he believed the report of its being removed by Judge Buller was wholly without foundation. On referring afterwards to Mr. Burt's notes to Carrington's poem on Dartmoor, I find he treats it as ' a calumny.' I believe that by our different conversations with Hannaford we have made him a bit of an antiquary, and I was no less surprised than delighted when he informed me that, only a few days before, he had brought home an oak that he had discovered in a bog, at a place called Broad-hole, on Bair-down. I have heard Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt say that he had found alders and willows in a bog near Tor Royal; but I do not remember to have heard of any oak being so found, at least of such dimensions. The tree thus discovered, which consists of the trunk, part of the root, and also of a branch, is ten feet long, and, at its lower extremity, is nearly five feet in girth. The whole of the trunk is perfectly sound, but not altogether so dark or solid as I should have expected: for generally, I believe, and particularly when it has been deposited in a bog, it is as hard and as dark as ebony. A branch of it had for some time been visible in the bank of the river Cowsick, and this induced Hannaford to examine it, and finally to exhumate it from the depth of eight feet. It is not improbable that this is a vestige of the antediluvian forest of the moor. Distant from Wistman's Wood about two miles, and by the side of another river, it could never have formed part of it; indeed it is probably larger than any there: and we have no account for ages of any other oaks existing on the whole of this extensive desert. A day or two after he brought it to Tavistock, and it is now in my possession.

"I learnt from him that some years since some oak bowls 7 were found in a bog, by a person called John Ash, between the Ashburton and Moreton roads.

"On crossing the bridge which was erected by my father over the Cowsick, Mrs. Bray expressed a wish that I would point out to her some of my inscriptions on the rocks below, which, from some strange circumstance or other, she had never seen; and even now I thought that, without much search, we should not have found them; not recollecting, after so long a period, where I had placed them. But, on looking over the parapet, she observed, on one of the rocks beneath, the name of her favourite Shakspeare. Perhaps, under other circumstances, it might have altogether escaped notice ; but the sun was at that instant in such a direction as to assist her in deciphering it, as it did some of our English officers in Egypt, who thus were able to interpret the inscription on Pompey's Pillar, which the French sçavants had so long attempted in vain. Many an officer (for a large body of troops had guarded, for years, the French prison on the moor) no doubt had visited Bair-down, and probably fished on the river, and yet these inscriptions seem never to have attracted their notice, nor, indeed, that of other persons; or, if they have, it has never reached my ears. But I have long been taught to sympathise with Virgil, when he exclaims -

' Rura mihi, et rigui placeant in vallibus amnes,

Flumina amem sylvasque inglorius.' - Geo. 1. ii. 485.

"Had my name been so renowned as ' virûm volitare per oras,' I doubt whether I should have experienced greater pleasure than I felt when my wife first discovered my inscription on the rock, and expressed the feelings it excited in her. I question whether, for the moment, she felt not as much enthusiasm as if she had been on the Rialto itself, and there had been reminded of the spirit-stirring scenes of our great dramatist in the 'Merchant of Venice.' I have somewhere read, that a philosopher having been shipwrecked on an island which he fancied might be uninhabited, or, what perhaps was worse, inhabited by savages, felt himself not only perfectly at ease, but delighted at seeing a mathematical figure drawn upon the sand; because he instantly perceived that the island was not only the abode of man, but of man in an advanced stage of civilization and refinement. It certainly was a better omen than a footstep; for the impression of a human foot might have excited as much fear, if not surprise, as that which startled Crusoe in his desert island. Perhaps I fondly had anticipated that, long ere this, on seeing these inscriptions, some kindred being might have exclaimed, 'A poet has been here, or one, at least, who had the feelings of a poet.' I would have been content, however, to remain unknown still longer, thus to be noticed, as I was by one so fully competent to appreciate those feelings which, no doubt, to most would have appeared ridiculous, if not altogether contemptible."

As, since the days of Sir Charles Grandison, it is quite inadmissible for ladies to write to their friends the fine things that are said of them, I certainly should have stopt short before I came to this compliment about myself. But my husband, who was pleased to pay it, insisting that, if I took anything from his Journal, I should take all or none, I had no choice.

Adieu, my dear Sir,

And believe me ever most respectfully

and faithfully yours,

Anna E. Bray.

Footnotes

1Vide Herodotus for the stones set up by Sesostris.

2Dr. Clarke when describing the Celtic remains at Morasteen, near old Upsal, says, "We shall not quit the subject of the Morasteen (the circle of stones) without noticing, that, in the central stone of such monuments, we may, perhaps, discern the origin of the Grecian (βῆμα) Bēma, or stone tribunal, and of the ' set thrones of judgment' mentioned in Scripture and elsewhere, as the places on which kings and judges were elevated; for these were always of stone."

3Mr. Polwhele says, in his Devon, "For the Cantred of Tamare we may fix, I think, the seat of judicature at Crockerntor on Dartmoor; here, indeed, it seems already fixed at our hands, and I have scarce a doubt but the Stannary Parliaments at this place were a continuation even to our own times of the old British Courts, before the age of Julius Cesar."

4Crockerntor is not entirely granite, it is partly, I believe, of trap formation. The following very curious passage from 'Clark's Travels,' vol. iv., will be found most interesting here: - "Along this route, particularly between Cana and Turan, we observed basaltic phenomena ; the extremities of columns, prismatically formed, penetrated the surface of the soil, so as to render our journey rough and unpleasant. These marks of regular or of irregular crystallization generally denote the vicinity of a bed of water lying beneath their level. The traveller, passing over a series of successive plains, resembling, in their gradation, the order of a staircase, observes, as he descends to the inferior stratum upon which the water rests, that where rocks are disclosed, the appearance of crystallization has taken place; and then the prismatic configuration is vulgarly denominated basaltic. When this series of depressed surfaces occurs very frequently, and the prismatic form is very evident, the Swedes, from the resemblance such rocks have to an artificial flight of steps, call them trap; a word signifying, in their language, a staircase. In this state science remains at present concerning an appearance in nature which exhibits nothing more than the common process of crystallization, upon a larger scale than has hitherto excited attention."- p. 191.

5"The universality of Celtic manners, at a very remote period, is proved by the existence of conical thatched houses, as among the Britons, and rude stone obelisks, adjacent tumuli, and Druidical circles, in Morocco."- Gentlemen's Magazine, July, 1831. Dr. Clarke, the celebrated traveller, gives a very interesting account of vestiges similar to those found on Dartmoor in Sweden and other northern counties. See the ninth volume of his Travels.

6An account of this ancient British monument was laid before the Society of Antiquaries by my brother, Alfred J. Kempe. It may be found in the twenty-third volume of the Archaiologia.

7Bowls formed of oak were used by the ancient Britons. Mention is made of them in Ossian : and in the Cad Godden, or the Battle of the Trees, by Taliesin, the following passage occurs: - "I have been a spotted adder on the mount"(alluding to the serpent's egg); "I have been a viper in the lake. I have been stars among the supreme chiefs; I have been the weigher of the falling drops"(the water in the rock basins), ''drest in my priest's robe, and furnished with my bowl."

Page last updated 21/03/20